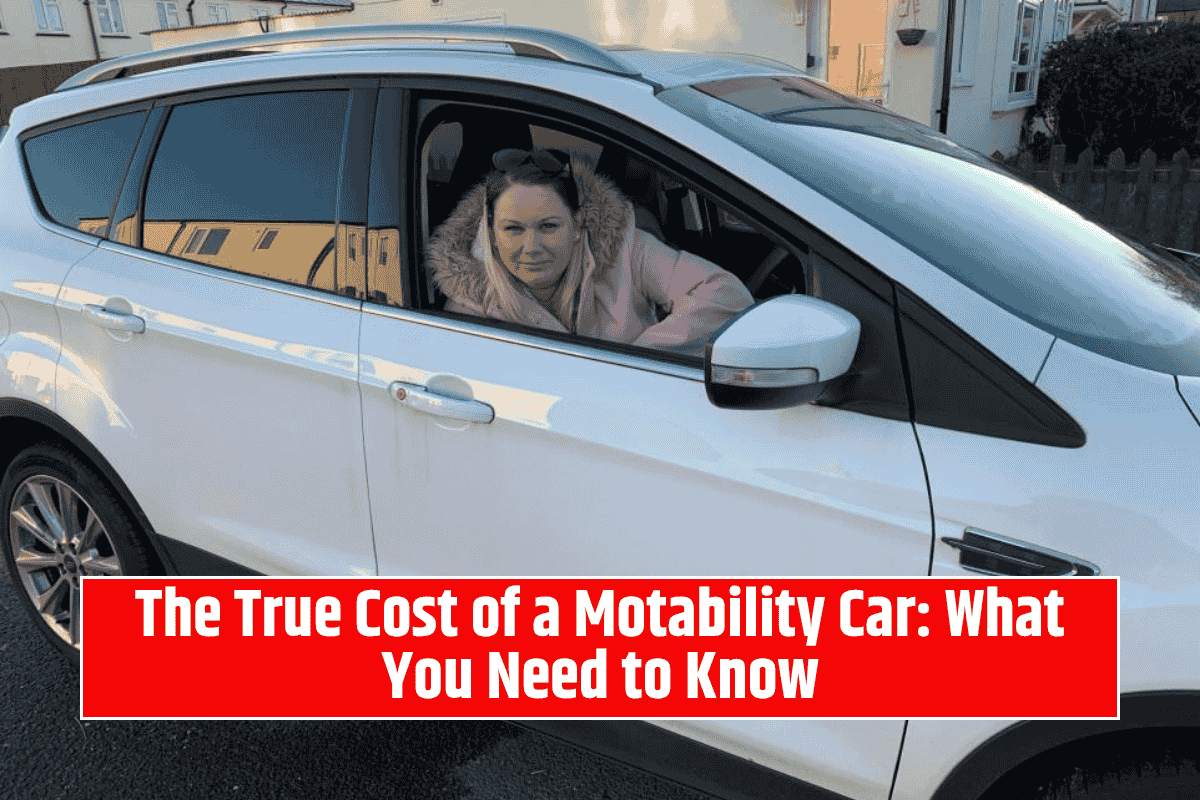

When discussions arise about Welfare Reform, one topic that often sparks debate is whether taxpayers should be funding cars for non-working people, especially people with disabilities. Some people don’t fully understand the real costs involved in the Motability scheme.

I want to take this opportunity to explain the true cost of my Motability car—not because I owe anyone an explanation, but because I want people to understand how much individuals with disabilities contribute to these cars.

Are Motability Cars Free?

The simple answer is no, Motability cars are not free. In order to qualify for a car through the Motability scheme, you need to have enough points on the mobility part of the Personal Independence Allowance (PIP) assessment.

Specifically, you must qualify for the enhanced rate. This benefit, however, is not means-tested. This means it is not based on your income or savings, which has led to debates about whether this system is fair.

Some argue that the cost of these cars can be too high for many people to afford without assistance.

Once you’re awarded the enhanced rate (currently £77.05 per week), you can trade this amount for a car. However, it doesn’t matter if you choose a small, medium, or large car—the full amount is used, and there is no extra funding.

The Hidden Costs: Advanced Payment

The biggest cost, which is not covered by the allowance or Motability, is the advanced payment. Think of this as a deposit, but with one key difference: you do not get this money back.

For example, if you’re getting a new car every three years (or five years for a wheelchair accessible vehicle), the advanced payment can add up significantly.

If you opt for a smaller car like a Toyota Aygo, the advanced payment might be zero, meaning you only pay the monthly allowance. However, larger cars, especially those that are adapted for specific needs, come with a much higher price tag.

For those who require more specialized vehicles, like myself, the costs are higher. For example, if you need a van to accommodate your mobility needs, the advanced payment can start at £15,000, and that’s before any modifications.

Extra Costs: Adaptations for Accessibility

In my case, I need to drive using hand controls, which is a specific requirement noted on my driving license. These adaptations come at an additional cost. The hand controls alone can cost an extra £5,000.

So, when you add it up, a van with no adaptations costs £15,000 upfront, and with the hand controls, that’s an additional £5,000.

That’s £20,000 in total for a vehicle that will only be in use for five years, after which I must return it and start the process again. For some people, the cost of a car and adaptations can be much higher—up to £35,000 or more.

The Bigger Picture: A Lifeline for Many

I’m not trying to sound ungrateful for the Motability scheme because, without it, I wouldn’t be able to afford a vehicle. For many of us, this scheme is a lifeline.

It provides us with the freedom to live independently, access work, and maintain connections with the outside world.

However, the scheme is not free. People with disabilities have to find ways to cover these costs, whether through grants, fundraising, or using their own savings.

It’s important to remember that the Motability scheme is not just about the amount of money spent—it’s also about the independence and opportunities it provides for people who struggle with mobility.

So, before questioning whether disabled people should have their cars funded by taxpayers, take a moment to think about the true cost.

For many, it’s not just about the money—they’re sacrificing their own savings and future financial stability to maintain their independence.